Let’s abandon NAPLAN – we can do better

Categories

Share

Nan Bahr, Southern Cross University and Donna Pendergast, Griffith University

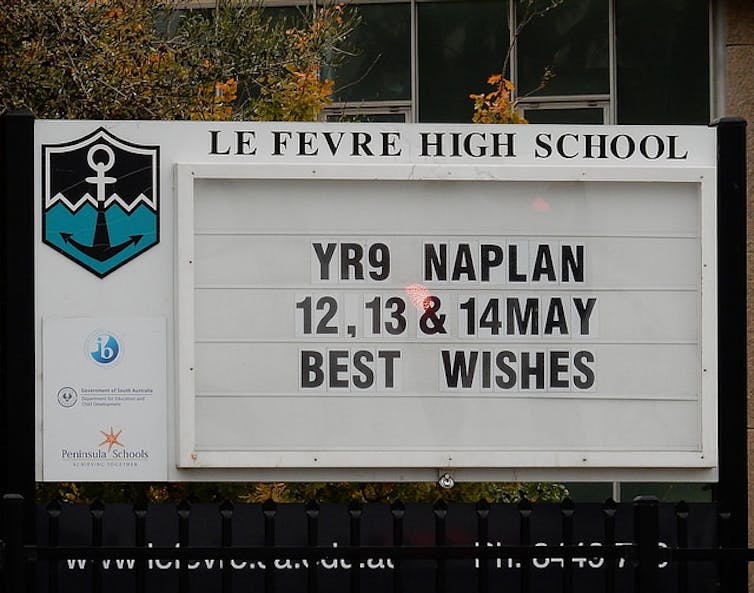

NAPLAN testing starts this week. With calls for a review, many education experts are calling the Future of NAPLAN into question. In this series, the experts look at options for removing, replacing, rethinking or resuming NAPLAN.

The National Assessment Program for Literacy and Numeracy sounds like it ought to improve literacy and numeracy. But it hasn’t.

Instead, it has been somewhat of a distraction for teachers, students and communities.

Since it’s clear NAPLAN hasn’t been an outrageous success, we suggest we ought to rest the program and adopt more continuous teacher-led evaluation methods that enable teachers to respond directly to students.

Why do we have NAPLAN?

NAPLAN is a series of tests conducted in exam conditions. The paper tests occur across three days every second year of a child’s schooling, in years three, five, seven and nine. The event occurs each May and results are provided about three or four months later.

NAPLAN was to be the path to learner excellence. Julia Gillard said, regarding the full introduction of NAPLAN across the country:

It’s important to the individual child and their parents to get a report card about how that child is going against national standards. It’s important to teachers; they do value this diagnostic information to work out what they need to do next for the children in their class. And we need it for MySchool, which is more information than the nation’s ever had before about what’s happening in Australian schools.

It was hailed as the process that would help teachers identify literacy and numeracy weaknesses and strengths. In doing so, it was to provide accountability for teachers for our students and our nation. And we could see how schools were performing.

These intentions were admirable, if not idealistic and entrenched in a strong accountability agenda. So, it’s time for us to move beyond NAPLAN to achieve aspirations that have currency.

Read more: NAPLAN testing does more harm than good

What’s the problem?

As educators in the teaching profession we have a few issues with the limitations and impact of the NAPLAN regime:

-

the tests provide information about student performance in narrow aspects of literacy and numeracy

-

it’s well outdated by the time teachers, parents and students receive it, as it can take up to four months for teachers to receive results from the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA), who designed and administer the tests. The tests are in May and according to the official NAPLAN site, are released to schools and parents somewhere between mid-August and mid-September

-

it assumes teachers are not using appropriate, in-time formative and diagnostic approaches as part of their repertoire of teaching

-

it often results in a change in school and classroom culture, with an emphasis on teaching to the test instead of more appropriate teaching methods

-

it reinforces a culture of sameness and lockstep achievement

-

it has led to gaming, where participation in the test is influenced in order to achieve certain outcomes. For example, students whose teachers expect them to struggle with the tests can withdraw them from the test, effectively removing them from the school’s performance profile for that year

-

it has created a generation of learners who have had the opportunity to fine tune a range of negative responses to the high stakes regime, including anxiety and physical illness.

There are other problems, not least the cost and time allocated to preparation, administration, analysis and reporting. But in summary, it fails in its goal.

But has it led to better student outcomes?

Well, not really. Any response to identified deficits will be quite delayed if teachers wait for the results before working to improve student capabilities. The results are not shared with students in a way to help them understand and direct their own efforts as learners. That is, the charts and graphs that map their achievement are not really designed for student consumption.

Change in NAPLAN performance over time shows there has been negligible benefit, even when we just consider the narrow set of capabilities under the microscope.

It’s reasonable to expect the year nines in 2017 would be doing a lot better than the year nines in the first run of the suite of tests in 2011. The 2017 year 9s have been the first cohort through to have experienced the entire set of NAPLAN tests from when they were in year three in 2011.

Yet, clearly writing has plunged, the first dip when the test changed from requiring a narrative to a persuasive text in 2012. Maybe numeracy has improved. Overall, there’s not a lot of support in the data for an argument of wholesale positive impact on student capability from this process.

Read more: NAPLAN is ten years old – so how is the nation faring?

Is it just us?

We’re not the first to question the efficacy of NAPLAN. The 2013 report into maximising our investment in Australian schools cited several witnesses to their inquiry who gave damaging accounts of NAPLAN. These were summarised in the report on page 17:

A number of witnesses raised specific concerns about NAPLAN testing arguing that the testing is expensive and encourages teachers to “teach to the test”.

But maybe the kids like it?

Sadly not. There have been numerous reports of students suffering from NAPLAN anxiety. Not all, of course, but why should we subject any children to needless anxiety?

Read more: Anxious kids not learning: the real effects of NAPLAN

Why do we persist?

Trying to view student achievement and to understand the quality of teacher performance through NAPLAN, at best, doesn’t help the students. At worst, it feeds a sense of public distrust for the teaching profession’s capabilities to diagnose, respond to and develop learners.

Gonski 2.0 helps us here, pointing to Australian schooling as being designed around a 20th century, industrial education model that is uniform throughout the 13-year program, including in assessment. NAPLAN is part of this culture.

Our teachers have the professional skills to understand and address the needs of the students in their classes. We need to kill the distractions and allow teachers to do what they do best.

This article has been updated since publication to fix an error is stating ACER who designed and administer NAPLAN. It is ACARA who does so.

Nan Bahr, Pro Vice Chancellor (Students)/ Dean of Education, Southern Cross University and Donna Pendergast, Dean, School of Educational and Professional Studies, Griffith University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/current-students/images/Coffs-harbour_student-group_20220616_33-147kb.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/current-students/services/counselling/images/RS21533_English-College-Student_20191210_DSC_6961-117kb.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/study/scholarships/images/STEPHANIE-PORTO-108-2-169kb.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/study/arts-and-humanities/images/RS20958_Chin-Yung-Pang-Andy_20190309__79I5562-960X540.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/experience/images/SCU-INTNL-STUDY-GUIDE-280422-256-72kb.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/dep-site-assets/component-library/screenshots/online-1X1.jpg)

/484x0:1516x1032/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2026/sirius.jpg)

/484x0:1516x1032/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2026/67800-yr-old-hand-stencil-5--2000px-x-1032px.png)

/484x0:1516x1032/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2026/Business-header.jpg)

/514x0:1487x973/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2025/Bondi-beach-view_credit-Azucena-Stelzer-on-Unsplash-G1-OXISVnqM-2000X973.jpg)

/540x0:1460x920/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2025/Georgina-Dimopoulos-SCU-COUNCIL-HEADSHOTS-17042025-133_2000px.jpg)

/484x0:1516x1032/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2025/2025-UniSport-Nationals_2000px-x-1032px.png)

/325x0:1925x1600/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/study/images/GC_080622-359.jpg)

/484x0:1516x1032/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2025/Collins-Hume-at-Northern-NSW-Buinsess-Awards_web-banner.jpg)

/484x0:1516x1032/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2025/JN_01474-AllWinners-2000X1032.jpg)

/484x0:1516x1032/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2025/SCU-2025-Hero-Psychology-B-Insitu-001-web_web-banner.jpg)