/1020x0:1671x825/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/Cave-art-site-of-Leang-Karampuang-in-the-Maros-Pangkep-karst-area-of-South-Sulawesi_credit-David-P-McGahan.jpg)

Share

Figurative rock art – art that presents lifelike representations of subjects – provides visual insights into ancient cultures, beliefs and societal practices, offering a direct window into human cultural evolution.

Being able to date figurative rock art accurately is crucial. It helps establish timelines of human artistic expression, aiding in understanding the development of symbolic thinking and cultural complexity across different periods and regions.

In an article published in the journal Nature today, we present a novel approach to date cave paintings.

Using this new dating innovation, we have found the world’s oldest figurative cave art.

Dated to at least 51,200 years ago, the art depicts an interaction between humans and a pig. It was found in a cave in Sulawesi, an island of Indonesia directly north-east of Bali and east of Borneo.

It’s a crucial piece of our history as humans, suggesting figurative art and storytelling have long been intertwined.

A new pioneering technique

In some limestone caves where people made rock art, dripping or flowing water occasionally led to the formation of mineral deposits on top of the paint layer, which provide a way to date the art scientifically.

Each drop of water leaves a tiny amount of carbonate particles, leading to the formation of a whitish coating over the rock art. The same process also leads to the growth of speleothem (also known as stalagmite and stalactite) layers, with numerous layers of particles that encapsulate all sorts of elements, including uranium.

Uranium is a naturally occurring radioisotope, meaning the chemical element will decay into other elements with time.

By comparing the ratio between the parent isotope (uranium) and the daughter isotope (thorium) we are able to calculate an age proportional to the time it took for the latter to form. This technique is called uranium-series, or U-series.

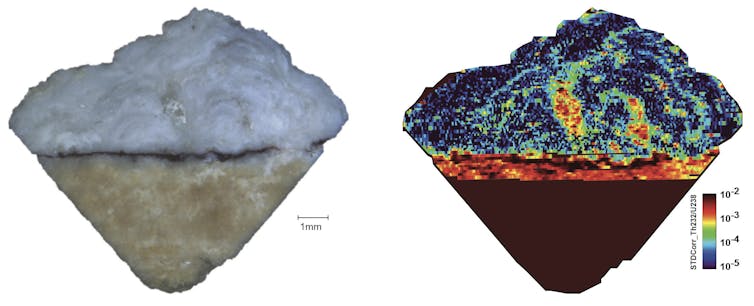

Rock art dating using U-series has typically been done by manually excavating a calcium carbonate sample and dissolving the resultant powder into a chemical solution, which is then introduced into a mass spectrometer. But the problem with this approach is that it averages several layers that have different ages, and does not distinguish pristine zones from altered ones.

To overcome these problems, our team developed a new analytical approach that uses a laser beam, four times smaller than the width of a human hair, to precisely sample the layers of calcium carbonate covering the art, including those closest to the painting.

The technique permits a better understanding of the internal growth structure of the calcium carbonate that formed on the art. This allows us to identify porous areas within these growths that complicate the dating process.

The laser is run across the samples in parallel lines, known as rasters. Once these are consolidated into a single high-resolution data set, we are able to understand the distribution of uranium and associated elements in great detail.

This technique is called “U-series imaging”, as it creates a map of the sample’s geochemical composition. We can then extract the data closest to the paint layer, providing a precise age estimate.

The dating result is always considered to be a minimum age estimation, given there might have been a delay between the creation of the art and the growth of the first calcium carbonate layers on top.

Art to tell a story

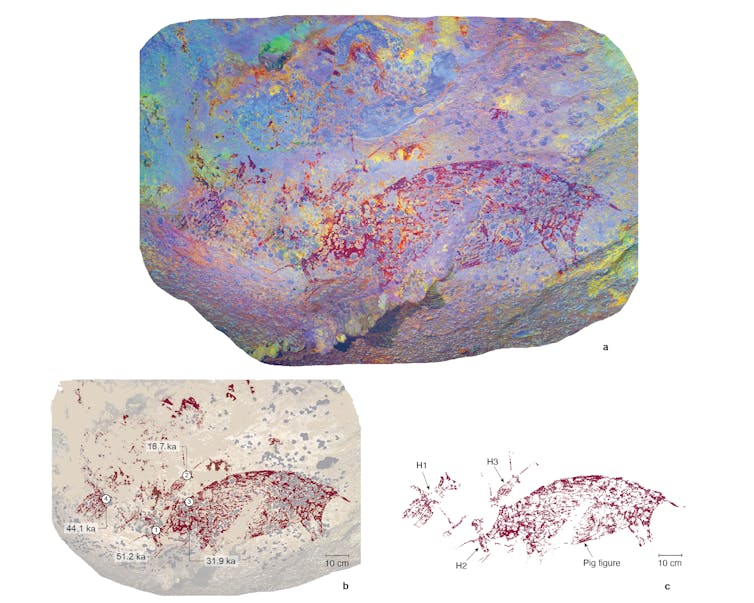

We used this new technique to date a painting in a cave in southern Sulawesi named Leang Karampuang and showed it is at least 51,200 years old.

The painting consists of a scene dominated by a large naturalistic representation of a wild pig. In front of the pig are three smaller human-like figures. They appear to be interacting with the animal.

One figure seems to be holding an object near the pig’s throat. Another is directly above the pig’s head in an upside-down position with legs splayed out. The third figure is larger and grander in appearance than the others; it is holding an unidentified object and is possibly wearing an elaborate headdress.

The manner in which these human-like figures are depicted in relation to the pig conveys a sense of dynamic action. Something is happening in this artwork – a story is being told.

We don’t know what that story was. Perhaps it was an account of a real boar hunt or a depiction of a myth or imaginary tale. Whatever the case, it seems to concern the relationship between pigs and people as conceived by early humans in Sulawesi.

We now know humans have used figurative art to tell stories for at least 51,000 years. Using our new dating method it may be possible in the future to fill in some of the many gaps in our knowledge of this key development in the history of art.![]()

Adhi Oktaviana, PhD Candidate in Archaeology, Griffith University; Adam Brumm, Professor of Archaeology, Griffith University; Maxime Aubert, Professor of Archaeological Science, Griffith University, and Renaud Joannes-Boyau, Professor in Geochronology and Geochemistry, Southern Cross University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Media contact

Sharlene King, Media Office at Southern Cross University +61 429 661 349 or scumedia@scu.edu.au

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/current-students/images/Coffs-harbour_student-group_20220616_33.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/current-students/services/counselling/images/RS21533_English-College-Student_20191210_DSC_6961.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/study/scholarships/images/STEPHANIE-PORTO-108-2.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/study/arts-and-humanities/images/RS20958_Chin-Yung-Pang-Andy_20190309__79I5562-960X540.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/experience/images/SCU-INTNL-STUDY-GUIDE-280422-256.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/dep-site-assets/component-library/screenshots/online-1X1.jpg)

/834x0:4167x3333/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/Lucas-Handley_Low-res-1a.jpg)

/484x0:1516x1032/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/grace-russell.png)

/256x0:1792x1536/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/12473932_10153551163870983_4881472587507230596_o.jpg)

/334x0:1667x1333/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/Bee-research_19072014_DSC_9193.jpg)

/514x0:1487x973/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/Coral-reef_credit-Wikimedia-2000X973.jpg)

/514x0:1487x973/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/Various-degrees-of-bleaching-in-corals-next-to-each-other-at-Lizard-Island-on-Great-Barrier-Reef_credit-Melissa-Naugle-2000X973.jpg)

/484x0:1516x1032/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/cyril-callister.png)

/334x0:1667x1333/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/matthew-henry-yETqkLnhsUI-unsplash.jpg)

/514x0:1487x973/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/Drone-flying-above-lagoon-at-One-Tree-Island_credit-Southern-Cross-University-2000X973.jpg)

/444x0:1557x1113/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/55b_Bellbrook_2000px.jpg)