/616x0:1385x974/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/Arthur-Jafa_Love-is-the-Message-The-Message-is-Death_video-still-2016-Courtesy-the-artist-and-Gladstone-Gallery-New-York_2000X973.png)

Share

Arthur Jafa’s Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death (2016) is, essentially, a music video. Currently on show at the Institute of Modern Art (IMA), Brisbane, it is also one of only a handful of video works in the world that could be called a masterpiece with a straight face.

Set to the booming rhythms of Kanye West’s Ultralight Beam (2016), Jafa’s work is seven-and-a-half-minutes of impeccably edited montages, most appropriated from the internet.

Black bodies in the turmoils and exultations of American life are shown striving, shuddering, dancing, fleeing, falling and in moments of reclaimed grace. Subtle repetitions – such as alien movie excerpts, police officers abusing their authority, the blistering surface of the sun – function as through-lines, grounding it in unconventional thematic registers.

Jafa elevates the music video while emulating the tenor of sports brand advertising. Sequences alternate between the prosaic and the universal; political reality and spirituality.

The majority of Jafa’s scenes are taken from amateur posts on YouTube, but others bear the watermarks of their IP owners (such as Getty Images, Amazing Space and Movieclips.com), as if in homage to the videos of Elaine Sturtevant, a pioneer of appropriation art.

The depths and virtuosity of Black identity

Love Is the Message begins with footage of a Black man, Charles Ramsey, who gained prominence for helping a white woman escape her kidnapper after being held captive for over a decade. He tells a reporter:

I knew something was wrong when a little pretty white girl runs into a Black man’s arms.

Scenes like this are imbued with racial division, which Jafa compiles like notes in a gospel score. They run adjacent to footage of some unequivocal geniuses of American culture: Nina Simone, Jimi Hendrix, Michael Jordan, Aretha Franklin, Serena Williams, Martin Luther King, Miles Davis and more.

These Black stars are shown in all their glory, but their presences are also tinged with melancholy; the shadow of great achievements born from social hardships, or of arrested potentiality.

Days after the presidential victory of Donald Trump, Jafa, at the ripe age of 56, first exhibited Love Is the Message in his New York solo debut. There it embodied public outrage over the 2014 deaths of Michael Brown, Tamir Rice and Eric Garner at the hands of white police officers, anticipating the then incoming government’s indifference to matters of racial injustice.

Described by critic Roberta Smith as “unbearably pertinent to our times”, Love Is the Message effectively relaunched Jafa’s artistic career.

Before then, he had spent years working as a cinematographer for Spike Lee, Julie Dash and John Akomfrah, amongst others (including second-unit work with Stanley Kubrick).

In recent years Jafa has expanded his practice beyond the realms of live-shot film and appropriated video. He now pursues his unique visual language through a variety of media, including oversized tyre sculptures and CGI projections, looking increasingly like a cultural archivist-turned-artist.

In all of this, Jafa examines the depths and virtuosity of Black identity, which, he asserts, is “an open ending”.

A time capsule

Eight years after its premiere, in the exhibition signage IMA director Robert Leonard situates Love Is the Message as a “time capsule”.

In 2024, we engage with the work very differently now that Kanye West, whose music is integral to its emotional core, is a controversial antisemitic symbol. Few saw this turn coming in 2016.

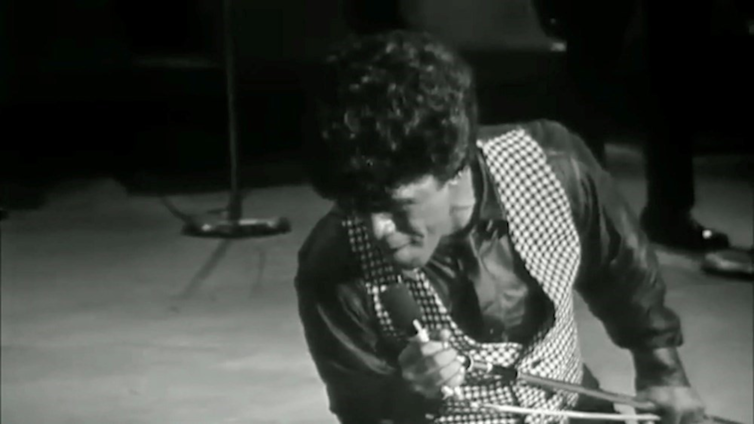

That said, even before the Kanye controversies, Jafa’s work was, in part, already dealing with the theme of greatness marred. Its closing scene is James Brown in concert – the soul singer who was arrested in 2004 on charges of domestic violence. In addition to this, Picasso, an artist central to debates about how we should discuss great art made by bad people, is specifically referenced by the album, The Life of Pablo, that Kanye’s song was taken from.

In this sense, Love Is the Message asks us to think about how we might separate our love for the art (the message) from any misgivings we may have about the artist (the messenger).

As time marches on and the work’s meanings shift, to my mind what resonates most today is its craft and conviction. There is its peculiar imagery and abstruse juxtapositions, the deathly gloom that hangs over its comical and ecstatic sequences, the surprising inferences of alien ontology.

Jafa has long been fascinated with the links between Black identity and alien symbolism. “Have you noticed that 2001’s monolith, Darth Vader’s uniform/flesh, and H. R. Giger’s alien are all composed of the same black substance?” he asks rhetorically in a 2015 essay.

Regardless of where we draw our moral lines, Love Is the Message is undeniably rousing; a love song to identity as an unrestricted thing, capable of being motivated by awe and rebellion.

While not particularly religious himself, Jafa “believes in Black people believing”.

His work presents spirituality as a counterpunch to anyone who wants to put people of colour in their place.

Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death is at the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane, until 7 April.![]()

Wes Hill, Associate Professor, art history and visual culture, Southern Cross University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Media contact

Sharlene King, Media Office at Southern Cross University +61 429 661 349 or scumedia@scu.edu.au

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/current-students/images/Coffs-harbour_student-group_20220616_33.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/current-students/services/counselling/images/RS21533_English-College-Student_20191210_DSC_6961.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/study/scholarships/images/STEPHANIE-PORTO-108-2.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/study/arts-and-humanities/images/RS20958_Chin-Yung-Pang-Andy_20190309__79I5562-960X540.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/experience/images/SCU-INTNL-STUDY-GUIDE-280422-256.jpg)

/prod01/channel_8/media/dep-site-assets/component-library/screenshots/online-1X1.jpg)

/514x0:1487x973/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/Youth-orchestra_credit-Roxanne-Minnish-on-Pexels-2000X973.jpg)

/484x0:1516x1032/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/kristie-harris.png)

/513x0:1487x974/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2024/Arthur-Jafa_Love-is-the-Message-The-Message-is-Death_video-still-2016-Courtesy-the-artist-and-Gladstone-Gallery-New-York_2000X973.png)

/932x0:4658x3726/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/Hype-Republic-Photo-4.jpg)

/337x0:1664x1327/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2023/Inevitability-2023.jpg)

/484x0:1516x1032/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2023/flow-1.png)

/484x0:1516x1032/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2023/gregory-smith.png)

/595x0:2125x1530/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2022/MicrosoftTeams-image-14.png)

/296x0:1477x1181/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2023/NORPA_LoveForOneNight_2022Season_photobyKateHolmes__211.jpg)

/342x0:1707x1365/prod01/channel_8/media/scu-dep/news/images/2023/332978408_228698276389222_6534426907451797532_n.jpg)